I know I'm probably not showing what I was feeling. I can look at myself, though, and really feel it. Damn.

So, the concert finished. Had to shake hands, meet and greet, do the thing, be the guy. Stayed at the front because Ed was in the back. Eventually I made my way back there. He was talking to a couple of people I knew had shown up just to hear his piece. Damn. I shook his hand, told him I was sorry. He was cool and totally supportive, as I knew he would have been even if it HAD been totally my fault. It didn't make me feel any better. I knew it had to be a disappointment, even if he wasn't really going to show me. I tried to believe everyone when they said I dealt with it with elegance and humor. I guess I did, but again, it didn't make me feel any better. To this day I have trouble dealing with it. Eddie and I normally speak or text quite regularly - maybe every couple of days, at least weekly. Since the concert I have basically ghosted the shit out of him. It's hard for me to get over. I feel the disappointment still.

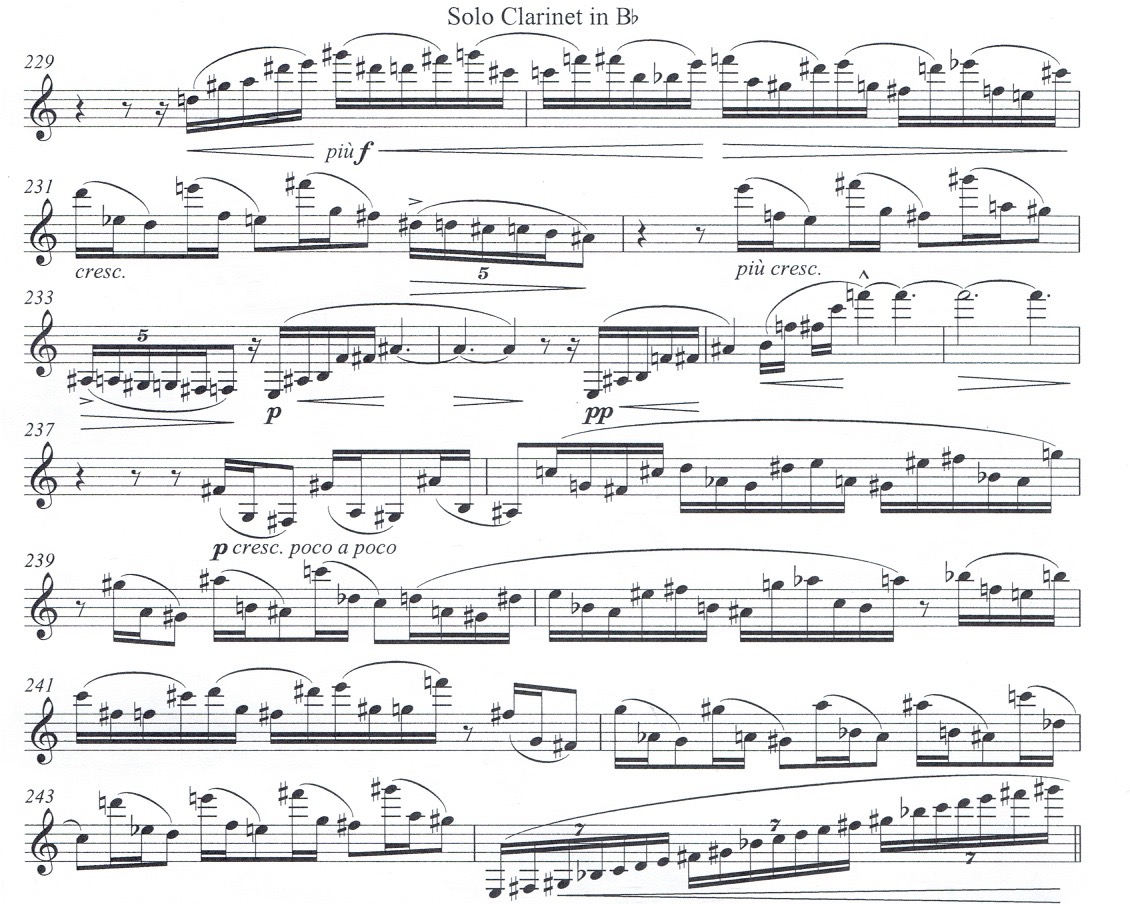

I shook more hands, I went to the bar, I got all my guys into a car back to Manhattan, and then I Googled the living fuck out of the pedal issue until about 2:00 in the morning. It was working again. What the hell? I decided that it was a bluetooth pairing issue, and that it had tried to randomly pair with someone phone and somehow screwed my connection. See, here's the problem: I had to come back the next day and play another show. I had planned to use the pedal because the piece I was playing (Davidovsky - Synchronism 12) stretches across five stands when using paper (it's not some odd format or anything, it's just that it's 14 pages over six minutes, and no time to turn pages - you just have to kind of lay them all out in a row). Again, that looks like shit on video. I fixed the problem with the pedal. I tried it over and over. 100% success rate. I went to bed. I woke up. I tried it a few more times. 100%. OK, the bluetooth was the problem. I'd just add a part to my talk where I ask everyone to turn off the bluetooth on their phones, boom. Problem solved.

Cut to 5:00. Show's at 7. It's been another crazy long day. I only have time to run through the Davidovksy, because we've spent all day getting good takes of Boulez with Scott. It's important, the run-through, because the Davidovsky has electronics and there are always issues of balance, etc. Check the pedal again. No problem. Sweet. Start the rehearsal, it's going fine. I go for the first page turn.

Nothing.

I lose it. I really lose it. Not AT anyone. Not TO anyone. But the emotions of the last couple of days, not to mention the months of planning that had gone into the damned thing, erupt out of me in the form of a lengthy, deeply blue, and oddly specific FUCK YOU to the gods, to the universe, to anything you might have on hand. Even on everyday occasions, I can swear with the best of them. Now I really pop the top off, like a barrel full of illegal fireworks. I have to get out of there for a second. I go out onto the street. A late October wisp of a mist is in the air, and it feels good. I take a few deep breaths, walk up and down the block. I gotta figure this out. I call my wife, tell her to bring my sheet music. I walk back in.

While I've been gone, the crew has figured out a jury-rigged solution to the problem: the left, or "page back" pedal, has always worked. They disconnect the cable from the right pedal, extend it a bit, and run it to the left. It works like a charm. That's the solution (and the source of the big "X" in gaffer tape on the photo at the top of the page) Should I trust it? I did mention before that I'm an idiot, right? Meanwhile it's 6:15 and Davidovsky has arrived and he'd like to hear the piece, because of course he would. Well, here's a chance for at least a real-world test. I play it, everything works fine. I'm rightly nervous about the tech, and it shows a little, but basically everything works. He tells me to play softer in spots. Cool. He doesn't know there was a problem. What problem? Time for the show.

Show starts and it's going well. It's becoming apparent, actually, that it's going REALLY well. It's like the stress and effort of the past couple of days fall away and we all say "fuck it" and just go out and play, and that's when the good stuff usually happens. The time approaches for Davidovsky. I wait backstage, clutching my horn and my pedal. Please work. One time.

I go out, make an intro at the mic, and then walk to center stage to do the thing. I start by myself. The electronics enter. The first page turn comes really fast. I cross my fingers (figuratively, obv) and hit the pedal with my foot.

yes

Oops. I make a mistake because the fucking thing actually works! Can't do that. I turn my focus to executing the piece, and everything turns out well. Everyone seems happy with it. I am relieved. I hit the mic again, introduce Scott, and sit down to assist with Adam. As I do, I see Eddie in the audience. He comes to both nights even though his piece is one on the first, because he's a mensch. I put a big smear of regret across my relief. Still, the concert finishes well and is an actual good time (I know, at a classical show! Shock!)

Cut to now. I return to speaking in past tense. So that's what happened. Two instances where I had to deal with truly difficult issues pretty much in real-time. The first key to overcoming things like that is preparation. Without hard, dedicated preparation you can never really get to the second key, which is trusting yourself. Without those two things, you can't achieve the end, which is to be able to forget mistakes or problems and be the best player and person you can. As I mentioned earlier, I'm not sure I could have gotten past those things so quickly when I was younger. I find that it's a skill like any other, and gets better with practice. Be prepared, leave mistakes behind, and be better in every moment moving forward.

I'm going to finish this one with a thought that's so good I wish it was mine. It's actually from Adam Neiman, who is a fabulous and wise pianist. As part of his preparation, he does as many full runs of pieces (that is to say, he starts at the beginning and plays all the way to the end without stopping) as possible. For some pieces, including concertos that run 30 to 45 minutes, his full-run repetitions number in the thousands. Pianists. . .Anyway, that is (almost literally) insanely prodigious. So I asked him about why he goes for that level of prep. He said (and I'm paraphrasing - it's been a few years), "well, everyone gets to that spot in a performance where you go 'oh, shit. What's next?'. The thing is to have the answer to that question".

The thing is to have the answer to that question.

And, Eddie, I'm not done with our piece in New York. Not by a damned sight. It's the next thing to overcome.